Behavior Change: Democratizing Design Strategies for Mental Wellbeing

By Stephen Parker, AIA, NCARB

Architect + Planner, SmithGroup

Editor’s Note:

Parker is an architect and planner at SmithGroup in Washington, D.C, focusing on behavioral health design. He is an At-Large Representative of the Strategic Council and co-convener for the Mental Health and Architecture Incubator and former YAF Advocacy Director.

The goal of mental wellbeing has risen in the public consciousness in recent memory. The current imbalance in our routines, from a nationwide work from home experiment to the continual low-level anxiety of an ongoing health crisis and its knock-on effects of stress-inducing events – economic uncertainty, political strife, social injustice – highlight the mental health impacts of the past year. While additional healthcare resources and a shift away from social stigmatization have an important role to play, so does design. Design organizations have begun to explore these issues and this past year, the AIA Strategic Council launched the Mental Health + Architecture Incubator, exploring this broad topic. Spatial impacts upon physical and mental health have been well-documented through evidence-based design research. It’s this peer-reviewed material that can translate beyond healthcare facilities to other typologies, especially residential settings.

New design research and prototypes for behavioral health facilities offer a number of tangible lessons that can apply to other building types. The more we can understand how space can positively, as well as negatively, impact human behavior, the better we can become as designers to work towards solutions. By focusing mental wellbeing before a personal crisis snowballs into something more severe, architectural design can be another tool to address mental health issues for a range of individuals, households and communities.

The concept of home has evolved, both for those of us that have the privilege to work remotely and those now spending more off-hours at home, with fewer vacations. Where we lay our head at night has taken on new roles and responsibilities. No longer relegated to sleeping, eating, and relaxing, households must also work, teach, and entertain for an indefinite period. And to find a sense of harmony in the chaos that was this past year. As our needs evolve, so too must the spaces we call home.

This has resulted in increased demand in home offices, gyms, school rooms, and recreational spaces, both inside and out. But how can these new and re-purposed spaces help us address our mental health needs? One overriding theme is choice. We can regulate our moods, lift our spirits, and temper our behavior through the choices of temperature, sound, sight, smell, and tactile feeling. We can design spaces, especially the homes we’ve been sequestered in, to aid in behavioral self-regulation and bolster our mental wellbeing.

Self-Regulation & Spatial Choice

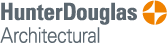

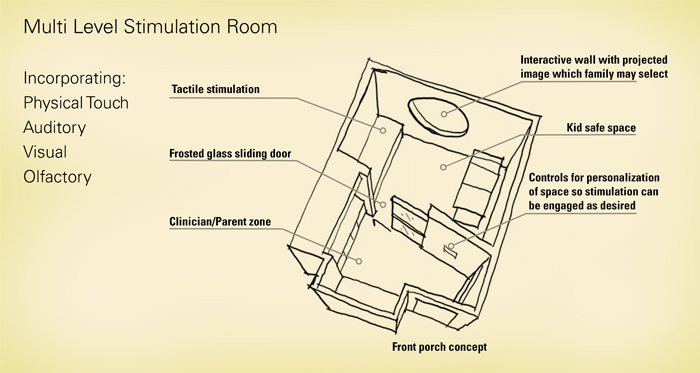

Self-regulation, the notion that by changing or adapting one’s environmental conditions a person can influence their cognitive function, mood, or other behaviors. In this manner, design has a role. Sometimes this can be as straightforward, such as reconfiguring a space with multiple seating options or work surfaces to choose from. Decompressing from a small space to a larger one or from an interior space to the outdoors can help individuals deal with stress in a way that works for them. This is seen in snoezelen rooms, as seen in some behavioral health and assisted living facilities, providing an array of sensory stimuli to help a patient self-regulate. So too can this lesson be used in homes or offices to address neurotypical individuals? Each person is different and design can be flexibly applied to accommodate a range of work, learning, and living styles with enough forethought.

One solution is often easily accessible: nature. Access to nature has been established by peer-reviewed research to provide a stress-relieving effect upon inhabitants of facilities that offer them. Brown, Barton Gladwell (2013) If the pandemic has taught us anything, it’s the value of this access to nature’s therapeutic effects. A balcony, patio, yard, or any other safe, outdoor space for people in extended lockdowns is of immense value.

When physical access to nature isn’t possible, there are alternatives. For the millions in apartment blocks and high rises, even visual access to nature can have stress-reducing effects. This visual access to nature (Lee, Sargent, Williams and Williams 2018), such as nearby parks can be beneficial. Taken a step further, the modern interpretation of the hanging gardens of Babylon can be found in examples such as Milan’s Bosco Verticale or Ivry-sur-Seine in Paris, with its balconies overflowing with plant life. This can provide a much needed visual reprieve from a dense urban environment. Some alternative approaches to integrating biophilic design principles can take the form of materials, patterns and even art.

Outdoor space, in general, is also stress-reducing and shifting behavior (Gueguen and Stefan 2016), so long as the outdoor space is of sufficient size and design to be of use to nearby residents. Parks and trails have the ability to decrease measurable stress levels in users after prolonged periods, including visual access. Confined spaces can visually “compress” a sense of place and so too can open spaces help decompress mentally. The integration of courtyards in healthcare spaces is a testament to bringing the healing effects closer to patients and has been replicated in homes for millennia. The courtyard homes throughout history were centered around trees that provided shade and evaporative cooling. Their ability to regulate their immediate environment, both physical and sensory, is a compelling design trend that has seen a recent resurgence for combating climate change as well.

Light helps regulate the activity cycle of humans, animals, and plant life. The presence of certain wavelengths and temperature ranges of artificial light can interrupt an individual’s sleep cycle, contributing to sleep disorders and other health implications, like with light that replicates a natural sun. When in confined space for extended periods of time, the lack of sunlight has negative effects on physical health which further impact mental health. In much the same way that Vitamin D deficiency has a debilitating effect on the body, so too can too much or too little of specific light frequencies, such as the commonly-cited electronic “blue light” that can contribute to insomnia in some cases. Providing control of light across the Kelvin range allows occupants to attune their environment to their needs. This helps regulate the sleep cycle as well as helps the mind focus for work or study periods. So too can light on streets provide a sense of safety and ambiance. Harsh, sterile light casts stark shadows while softer, more pedestrian-oriented street lighting can enliven a neighborhood.

Sound design is often an overlooked part of architecture, especially since it’s known to induce stress when designed poorly. Mitigating unintentional, distracting, and unwanted noises reduce cognitive fatigue and help motivation (Jahncke et al., 2011). In the same way that the beeps and ambient noise of a bustling hospital keep patients awake, distract caregivers, and generally elevate stress, so too can distracting noises of a full household. Children learning online, or your partner taking conference calls–this cacophony can be mitigated. Prescriptive approaches for healthcare facilities have been outlined in great detail, and many lessons can be gleaned from translating these ideas into people’s home environments – acoustic control, sound mitigation, and vibration isolation are but a few.

Studies have also shown that olfactory exposure to scents from both cultivated and wild gardens has a therapeutic benefit. This release of dopamine in the brain from the effervescent scents of a living forest, sap, fauna, and the biome of a wild environment. Even the aeration of soil in the air after a fresh rain has an almost indelible smell that’s easily recognizable. For some, this may trigger memories or a sense of nostalgia. Studies have linked the strengthened sense of smell to helping individuals orient themselves in space, especially those with memory issues.

Spatial Adaptation & Multigenerational Homes

With many families creating “pods” during the pandemic, a number of scenarios have resulted in packed households. Whether it’s their children experiencing distance learning, recent graduates moving back in with parents, or looking after elderly loved ones during this trying time, three-generation homes are seeing renewed interest. This helps overcome the social isolation many have felt since the pandemic. Once idle living spaces have adapted by rehabbing, renovating, and expanding at an unprecedented pace. Basements have been converted, spare bedrooms repurposed and garages updated to handle changing spatial requirements. Creating a sense of community goes a long way towards feeding the social bonds we all need for our mental wellbeing.

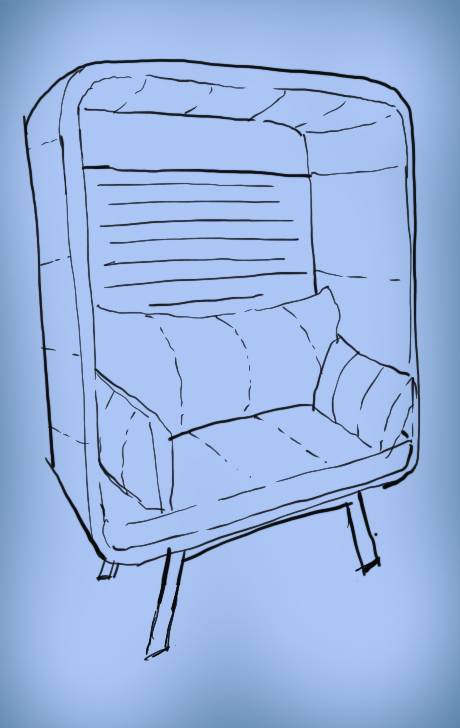

Spatial Choice learning environment sketch – offering a variety of seating and styles to accommodate varied learners within one space

Dignity Through Design

One such concept is designing with dignity. This can mean little things, such as controlling the temperature in one’s space individually. In the same way, a chilly office or sweltering conference room makes concentration difficult. As well, lighting and sun exposure control is small but impactful changes one can make to a newly repurposed home office or classroom. This could include simple examples such as personal space to call your own in the hectic mess of an entire household working, learning, and living on top of one another. This idea has permeated senior living and mental health facilities, and the incorporation of universal design principles for aging-in-place can allow homeowners the freedom to live as independently as possible in their own homes. This speaks to dignity and respect as drivers in the design process, which everyone, from clients to architects, can benefit from.

As mental health awareness and its effects grows, so too can design solutions driven by data, experience, and means testing. Design can play a role in mitigating stress, aiding in self-regulation, and giving families and individuals greater choice in adapting the space they call home for mental wellbeing, both now and into the future.